A small matter-of-fact voice

Our MARCH read

Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov, is a book written with both beauty and horror. We are led away from our morals and into empathy through the charm and sophistication of our story-teller.

From a leadership perspective, this novel challenges us to listen for the small, matter-of-fact voice within the story. It also asks us to open our minds to how transference creates a blueprint that can sometimes lead us astray.

This novel opens with a fictional psychiatrist, however let me lead this piece with the words of a psychologist who describes fiction reading as ‘a flight simulator for your mind’. Lolita is a story mapped out by a manipulative and unreliable narrator, and the journey he takes us on that diverges very far from the path of truth.

Book image by me. I could not find a cover to match the rawness and sensitivity of the story.

I later read in a CNN article that Vladimir Nabokov had written:

“… let us settle for an immaculate white jacket (rough texture paper instead of the usual glossy kind), with LOLITA in bold black lettering.”

I agree.

A murderer’s memoir

Lolita opens with a foreword from a fictional psychiatrist presenting us with the memoir of a murderer, Humbert Humbert. A charming and intelligent man, Humbert seeks a connection with the reader as he describes his all-consuming love and desire for a young girl. Humbert’s unreliable narration is finely selected, presented to distract you from the “small matter-of-fact voice” which tries to be heard.

It sounds like a storyline irresistible to Freud. The study of a fatherless and sexually promiscuous girl and a middle-aged man. Expect it is not. Freud’s thread of thought is the exact trap that Nabokov lays so skilfully with Humbert’s voice.

Nabokov & FREUD

Nabokov despised Freud, calling him a ‘a comic writer’. Bringing the two of them together may risk being haunted by disgruntled ghosts for a week or two, but I am sure it will be worth it. It is powerful to read Nabokov’s writing alongside a concept attributed with Freud, and even more impactful for understanding a Freudian concept in leadership theory.

Transference. A concept proposing that each time a person meets and interacts with someone new, the new relationship is formed as a new version of previous relationships. Unconsciously, individuals project their experienced emotions and behaviours with others in their lives – particularly in the case of authority figures – onto any new relationship. To find the truth in Lolita, and to remain alert to unreliable narration in leadership, we need to understand transference.

Seen through different eyes

“She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.”

Lo, Lola, Dolly, Dolores, Lolita. Have you heard the saying ‘a loved child has many names’? An idiom that is entirely misleading in relation to this particular child. Early relationships help to form a person’s identity and self-esteem.

“... (her mother) had underlined the following epithets, ten out of forty, under ‘Your Child’s Personality’: aggressive, boisterous, critical, distrustful, impatient, irritable, inquisitive, listless, negativistic (underlined twice) and obstinate. She had ignored the thirty remaining adjectives, among which were cheerful, co-operative, energetic and so forth.”

I feel complicit with Humbert’s crime when I refer to her as ‘Lolita’, and the strong emotional reaction is part of the strength of Lolita and the power of the novel to create discomfort and self-discovery.

From here, I will refer to her as “his Lolita” when identifying with Humbert’s obsession with her, and “Dolly” when I refer to the echoes of her own story as a 12-year-old girl.

Lo, Lola, Dolores

The lost child

Throughout the novel, Humbert uses the name Lo, Lola or Dolores whenever she amuses, annoys, exasperates and baffles him. The situations he uses these names are when he is conscious of his role of responsible adult, and this is a child developing in an environment of fault-finding, control, threats, bribes and abuse.

Dolly

The hidden child

In her own world, she is not Lo or Lolita. She calls herself ‘Dolly’. The childish name brings to mind a childish plaything, and it is the name used when she is with other children and their parents, teachers. Dolly is also a person Humbert must share with others, and one who requires him to take on a fatherly role. It is also the child who learns that adults are not dependable and that sex is transactional.

Lolita

The fantasy child

Lolita is a creation of Humbert’s and the name used during moments related to us as agonising desire and love. He creates a person who does not exist. Lolita can be considered the personification of his obsessive desire.

Sexualising a 12-year-old for profit

Did you know the book Lolita has over 210 different cover designs? Some designs tend towards painfully plain while many others are sexually provocative or suggestive. The author, Vladimir Nabokov, specifically requested no images of young girls on the cover and publishing houses doubled down on focusing on profit. The more provocative covers sold the most books, but it also helped to distort the message of Lolita.

Dirived & Distorted Messages

Dolores is a name with the meaning “sorrow” or “pain”, and Lolita is one of many derivatives or pet names. Since Nabokov’s novel the noun ‘Lolita’ has been reduced in popular culture to symbolise sexual promiscuity and young girls described with synonyms such as nymphet, vixen, seductress and vamp. Why? How can a story of a sexually abused 12-year-old girl be solidified into our language in that way? The noun ‘Lolita’ should mean obsession and abuse – a child controlled by person they idealise or see as an authority figure.

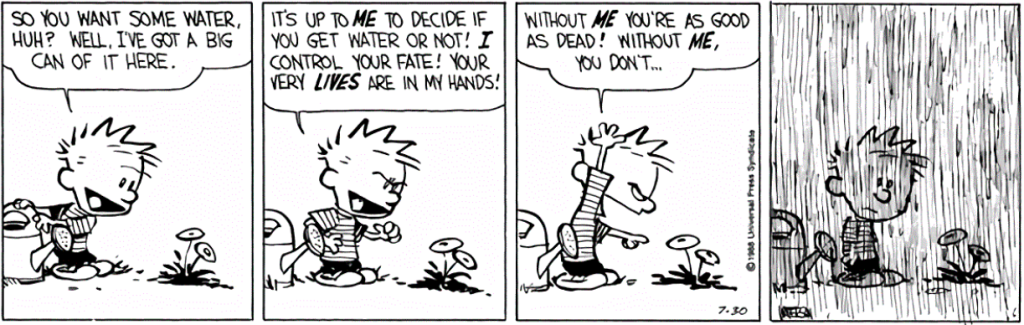

Authority is not leadership

Let me be very clear, Humbert Humbert is not a leader. This is not the perspective we are taking in this discussion – in any shape or form. He is a man driven by his own desires and need for control. As an adult, Humbert has a position of authority over a child and his influence grows in power when he steps into the role of guardian. Humbert’s presentation of himself as sophisticated, superior of intellect, and charming is a strategy that makes the most of transference.

Transference as a strategy

At the end of the novel, I asked myself how I could have let myself believe the story of a paedophile? And how I could I have so little compassion for a 12-year-old girl? It fascinated me to see how an unreliable narrator can influence our perceptions and emotions.

Humbert plays the reader by making it difficult to empathise with Dolly. His Lolita is described with such love and beauty, that the real life Dolly becomes vulgar and shallow in contrast. Despite seemingly sympathetic to her character weaknesses, Humbert merely reaffirms the negative traits within a sympathetic tone of an adult who knows better and is trying to help an ungrateful child. He assumes a role of authority – balancing his grandiose self-beliefs with self-deprecating insights to make him appear more humble. In addition, Humbert places his actions under the warm-tinted glow of romance, while others are left in the laboratory-white glare of scrutiny. As a reader, we respond to Humbert because of the filters we choose to apply.

How does transference become a filter

It may be difficult to empathise with his Lolita or Dolly, but the concept of transference brings at least understanding to this difficult character. As mentioned earlier, transference is a term coined by Freud to suggest our past relationships and experiences – particularly those with early caregivers – are projected onto our subsequent relationships. The way you and I, the way Dolly and the adults around her have experienced authority, control, care and love – according to transference – creates a blueprint for our future relationships. Particularly when authority is involved.

blueprints can be used unethically by leaders

Research does consistently show that relationships are formative and impactful on a developing brain. When we consider how our brains continue developing until our early-20s, it is interesting to see questions raised about the ethics of corporate leadership development programmes for graduates. Graduate programmes often have strong elements of elitism and competition, and the observation or close mentoring of an authority/power figure. The threat of exclusion, removal, or disapproval by authority figures is stronger amongst young people who are still forming personal experiences with authority or power figures. The impact of these experiences on future decisions is what we see within Dolly’s storyline.

Lolita-ship

In leadership, transference impacts people and results when individuals (sub-consciously) project past experiences onto those in authority. A person in a position of authority or control might not always be viewed through an objective lens, and the resulting behaviours and reactions can be filtered through idealisation or criticism rooted in the observer’s previous relationships (transference). This can affect the effectiveness of the leader. If we turn our eyes to Lolita, we will see adults responding to Humbert’s charm-filled presentation of authority and expressed intelligence. In a society that respects a person presenting themselves that way, the adults are primed to behave in a way Humbert expects.

You are impacted by transference

Humbert also uses transference is with you, dear reader. You and I have been primed through life to judge certain characteristics and behaviours as attractive or repellent. Dolly is illustrated in unlikeable while his Lolita is described as sexually promiscuous and spoiled. Instead of seeing it as a foil to offset his own repellent characteristics and behaviours, we believe the message. However, when we put the lens of transference on Dolly, Lolita becomes a completely different novel.

First, Flip the narrative

Dolly is a disappointing character. As a child she is shallow, and as she grows to womanhood, she reveals herself to be self-serving, emotionally flat and transactional in relationships. However, when we pick at the threads of Humbert’s story, small facts ooze through his words. A 12-year-old who lost her father young to suicide and her relationship with her mother complicated by criticism and disinterest. The combination of loneliness and innocence that leads her into situations with older teenagers and adults. When Humbert dwells on their passion and deep love, he also lets slip how she cries at night when she thinks he is asleep – remarking on her moodiness and his generosity in trying to keep her happy. Dolly is also described as being materialistic and demanding rewards for sex, while he reveals at the same time her reluctance to participate in his desire and her capitulation to pressure and bribery. She is greedy and shallow as she negotiates monetary bribes, sly and secretive for hiding the money for escape.

Second, Consider the impact of transference

These glints of truth are scattered and sometimes lost amongst Humbert’s magniloquence, making it a treasure hunt for the truth. When you take those threads and weave them outside of Humbert’s version, you start to see how Dolly’s actions and decisions are tainted by what she has learned from adults who failed to protect and guide her. She is still disappointing and shallow, but when we consider what she has learned about relationships and authority in her young life, we can begin to mourn her childhood and understand her responses and reactions.

Why did you not just leave?

In leadership, people’s subconscious transference can become as hidden and lost in the everyday as Dolly’s experience becomes in Lolita. If Freud is correct and our past relationships impact how we interact with authority figures, leadership theory suggests that the effectiveness of a leader can be affected by people’s projections of earlier relationships.

Why did you not see what they intended?

An individual with a blueprint of idealising and submitting to authority sets a pathway for a leader to build a dangerous ego. Humbert achieves power only through an increasing confidence in himself and his desires. Dolly observes a handsome stranger who treats her with friendliness and attention, his charm and appeal creating a power imbalance with her mother and other adults. If for years, Humbert manages the perceptions and influences of adults, it is understandable that 12-year-old Dolly would mirror adult reactions. In the void of healthy and supportive relationships, Dolly learns not to trust authority and to approach relationships in an emotionless and transactional manner.

Transference is a red flag

Transference serves us best when it is identified. Understanding transference allows us to better navigate the dynamics in our relationships that occur subconsciously. Lolita invites us to look beyond the surface, to question the narratives we are told and to be more mindful of the psychological forces at play in any relationship. Through the ‘simulation’ Nabokov offers us an understanding of transference, and with it, an opportunity to hold our past relationships accountable and to clearly see each new relationship we have the opportunity to build.

How to read Lolita

Forget his Lolita, and look for Dolly. Take note of her the few times she manages to tear through Humbert’s grandiose and emotive language. Do not let Humbert distract you. Side-step his game of manipulation and take note of when you find yourself charmed or repulsed.

I was a young adult when I read this novel, and vividly remember the disgust I felt when I realised how astray Humbert had led me. It was alarming to find myself trying to rationalise his actions to better align with my morals. Fascinated, I put Lolita on the shelf but Dolly proved to be a restless ghost. The second time I read the novel, I was able to hold myself distant and hold onto the 12-year-old child as her story slipped into the foreground.

This is how I recommend reading Lolita – with self-awareness of when (and how) Humbert triggers your empathy, dislike, judgement and forgiveness.

denied inspiration

Beneath Nabokov’s Lolita are significant similarities to the case of Florence Sally Horner. Sally was an 11-year-old girl kidnapped and abused for 21 months by a man who presented himself in a position of authority. Nabokov denies the case inspired his novel, despite referencing it in Humbert’s words:

"Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?"

Lolita opens with a foreword by a fictional psychiatrist. He writes to the reader to explain the story is Humbert Humbert’s memoir after his death in prison. Nabokov and the fictional psychiatrist warn us in the first pages that we need to be alert to the awfulness of the story and the foreword ends with the sentence:

“‘Lolita’ should make all of us – parents, social workers, educators – apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world.”

Despite the warning, we are swept along by Humbert’s influence. The first part of the story focuses on Humbert’s background as a child and youth and into adulthood. It describes his manipulation, charm and growing obsession as he navigates his desires for young and vulnerable girls. After moving into Dolly’s home as a boarding guest, his obsession focuses singularly on Dolly and we see his desperation to possess her. The first part of Lolita culminates with both intentional and chance events resulting in Humbert becoming her guardian, sealing her fate:

“You see, she had absolutely nowhere else to go.”

Inspiration to madness

The second part of the novel feels like a slow descent into madness. Here, Dolly’s reluctance to play the role of his Lolita is described by Humbert through accounts of her moodiness, coldness towards him and the bribes she begins to negotiate.

Humbert becomes increasingly suspicious and controlling. Despite his declarations of love he progresses from distress over schoolgirl bruises to cruelly backhanding her in his anger. There are heartbeat moments – short sentences tearing away his perception to show Dolly’s reality – tears, reluctance and seeking paths of escape. It is not the star-shattering love Humbert wants us to believe. She did have absolutely nowhere else to go.

It is our obligation to remember the physical and cognitive immaturity and development that is normal at her age, and to the authority and responsibility of adults to do protect a child during that development. And as Dolly grows up in the second part of the novel, to remember transference and how her painful experiences with authority figures form her future relationships and life.

Madness to silence

Dolly’s story ends without her voice ever being heard. If Lolita was written from her perspective, how would the story unfold? How many unheard voices can we pay attention to? Can transference help us listen to find the true story running beneath the narrative we are offered?